Happy Juneteenth, everyone! Today marks the first celebration of Juneteenth as a national holiday, and it's about time.

Juneteenth celebrates the end of slavery in the United States. It has been observed on June 19 since 1866 and postdates the Emancipation Proclamation by four years. Just this week, President Biden signed a bipartisan bill establishing the national holiday.

The origins of this holiday, like Independence Day, is rooted in war. Independence Day celebrates the United States declaring its independence from England. However, Juneteenth celebrates something far more fundamental; a people realizing their independence from another people.

Alexandria, Virginia, finds itself uniquely at the center of this tension. It played dual roles in the battle over slavery. First, it was a top national center for the sale of enslaved people. Second, its conquering by the Union Army first, before any other town, represented one of the most significant breakthroughs on the journey to freedom for enslaved people.

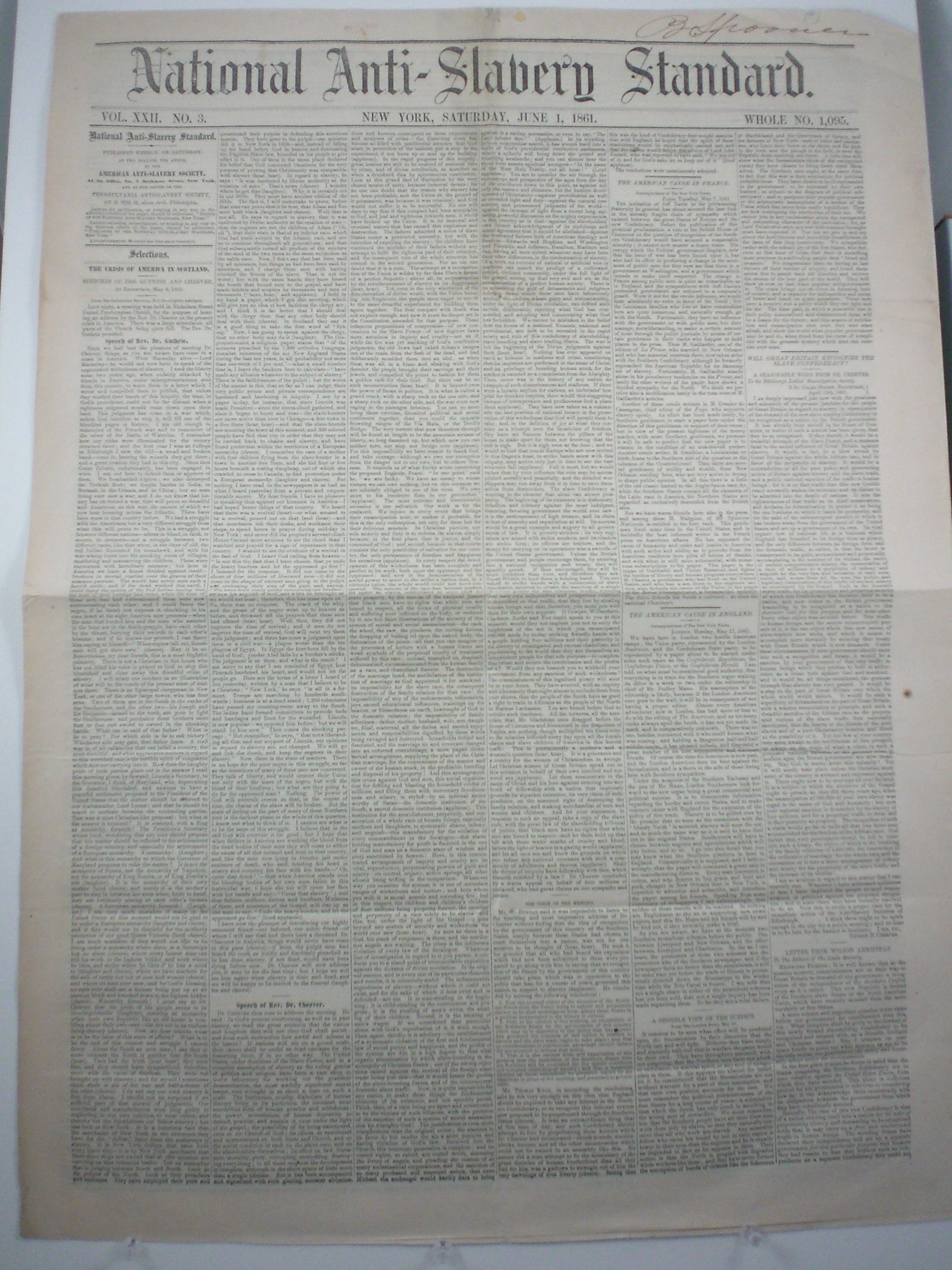

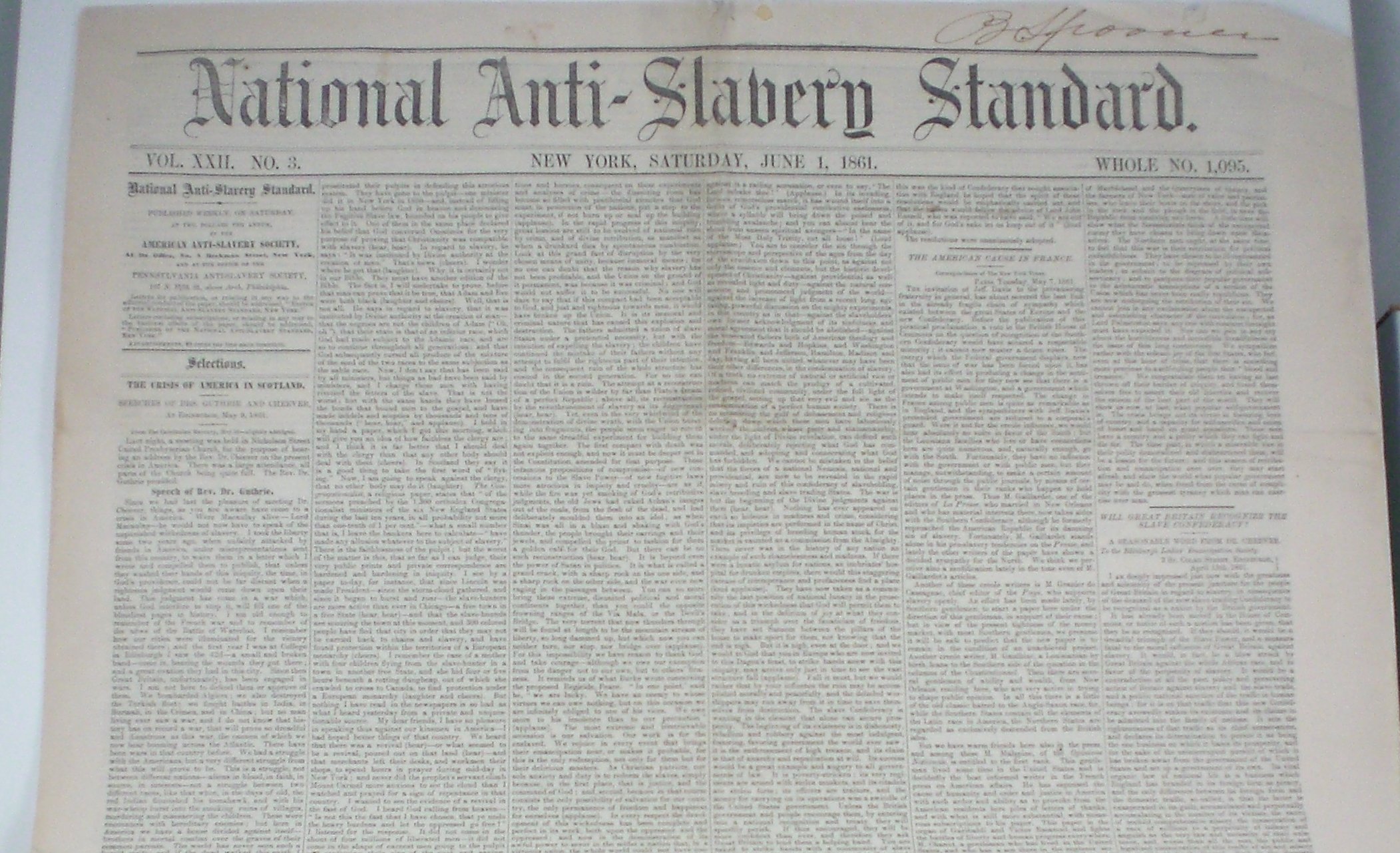

The June 1, 1861 National Anti-Slavery Standard article transcribed below vividly describes the experience of visiting Alexandria's "slave prison" as a person opposed to slavery. That building is now the newly updated Freedom House Museum, and it is set to re-launch in the fall. For those of us in Alexandria, Virginia, it will be something to be proud of. The museum sits in what was the largest enslaved person sales operation in the United States.

Here is a very memorable and emotional excerpt from the article transcribed below describing 1861 conditions inside the "slave prison" a week after the Union Army took Alexandria:

Who can tell how many tears have moistened, how many sighs and prayers have startled the rayless gloom of those dampened vaults; how many broken hearts and curbed spirits have been chained to this cold floor, for the commission of no crime, by the decree of no tribunal, but only because man claims ownership in man.

No matter how many times I read that short article, I can't read that paragraph without tearing up.

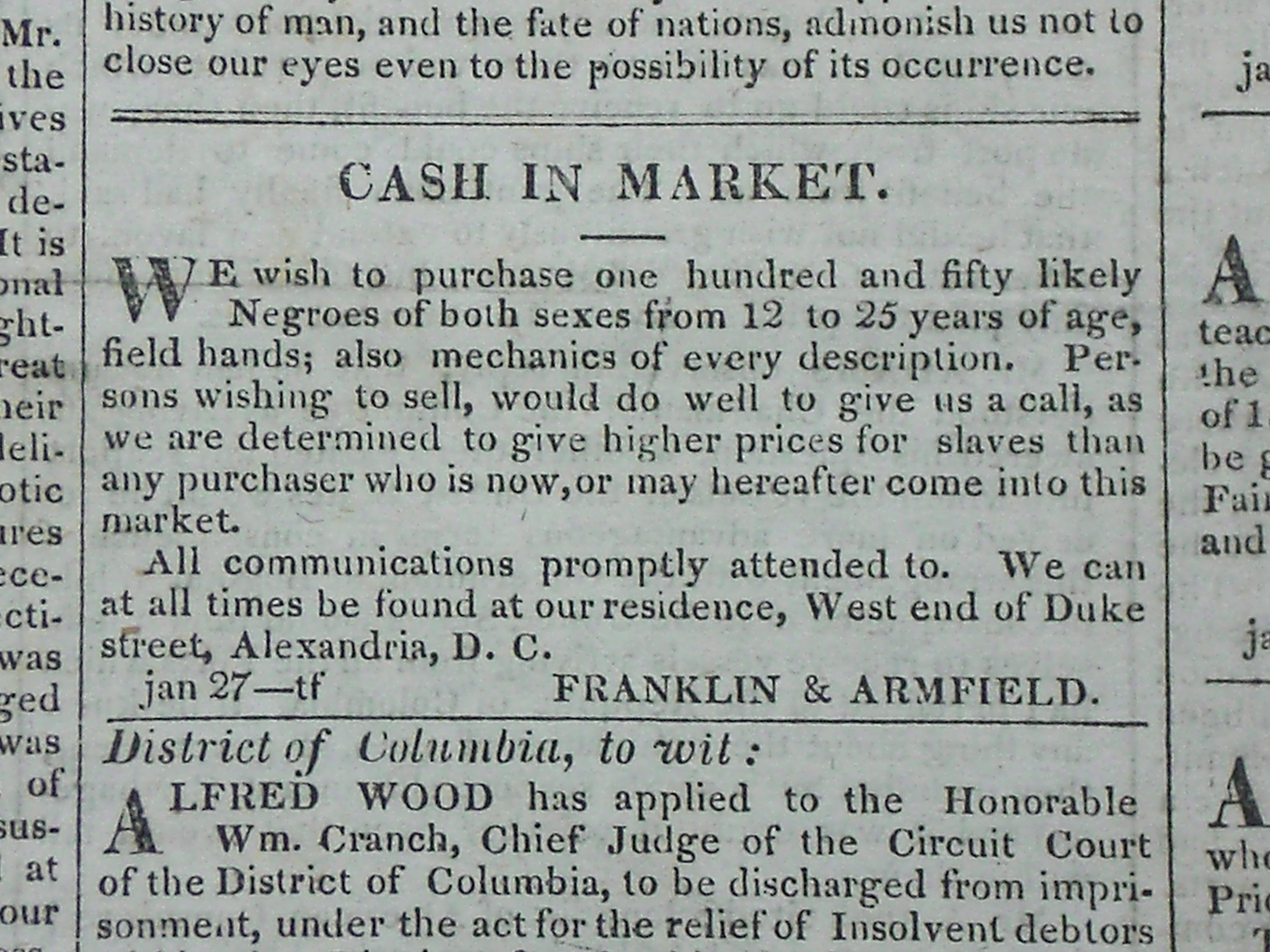

Several slave dealers operated out of the same building at 1315 Duke Street in the 1800s. The first was Franklin & Armfield from 1828 - 1836. The last was Price, Birch & Co., which operated from 1858 until the Union Army arrived in Alexandria in 1861. The unfortunately incredibly successful Franklin & Armfield operation was described in more detail by Wikipedia:

The property then extended further east, and they added structures for holding and trading in slaves. They also provided, for 25¢ a day, housing in their jail for slaveowners visiting Washington. The two-story extension to the rear of this house was part of the slave-holding facilities, which included high walls, and interior chambers that featured prison-like grated doors and windows. Franklin left the business, starting in 1835, and Armfield sold the property to another slave trader in 1836.

Franklin and Armfield sold more enslaved people, separated more families, and made more money from the trade than almost anyone else in America. They amassed a fortune equalling billions in today's dollars (2021) and were two of the nation's richest men. Franklin sold slaves from an office in Natchez, Mississippi, with branch offices in New Orleans, St. Francisville, and Vidalia, Louisiana. His uncle Armfield handled the supply, sending agents door-to-door in Virginia, Maryland, and Delaware looking for enslaved people their owners might like to sell, and arranging transportation.

Here's more about the National Anti-Slavery Standard according to Wikipedia:

The Standard was a weekly newspaper that was published concurrently in New York City, New York, and Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (1854–1865). It published essays, debates, speeches, events, reports, and anything newsworthy that related to the question of slavery in the United States and other parts of the world. Its audience was the members of the American Anti-Slavery Society and abolitionists in the north. Its two key focuses in the elimination of slavery were religion and politics, which considered slavery as an evil institution. Its strong religious appeal asserted that God was the only being that could end slavery. However, they did assign value to political action.

This transcription below is a very appropriate read for today. It's a reminder of what we left behind and why we fought a war that killed 750,000 Americans.

Transcription appears below:

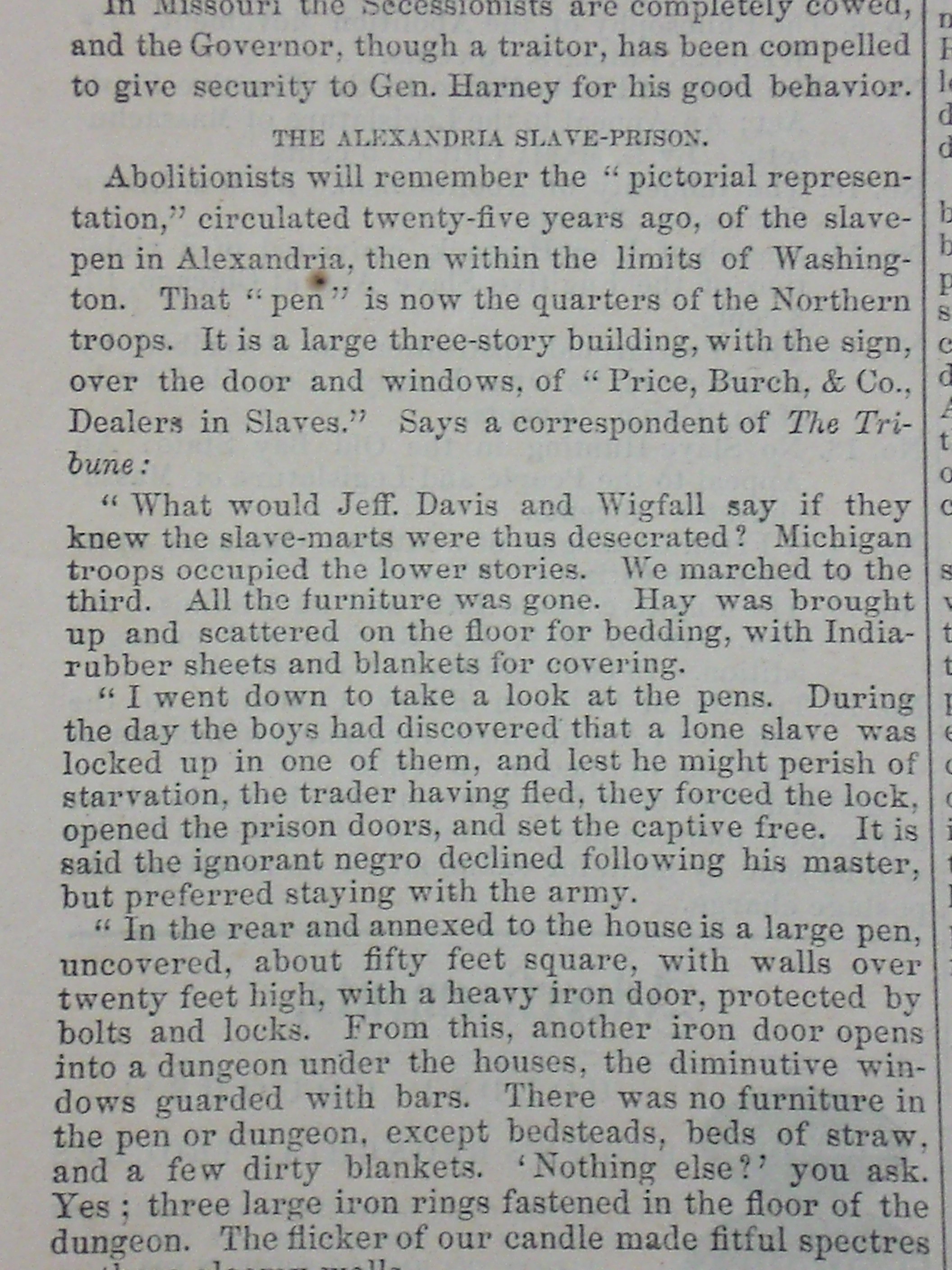

The Alexandria Slave–Prison.

Abolitionists will remember the “pictorial representation,“ circulated 25 years ago, of the slave pen in Alexandria, then within the limits of Washington. That “pen“ is now the quarters of the Northern troops. It is a large three-story building, with the sign, over the doors and windows, of “Price, Burch, and Co., Dealers in Slaves.“ Says a correspondent of the Tribune:

“What would Jeff. Davis and Wigfall say if they knew slave-marts were thus desecrated? Michigan troops occupied the lower stories. We marched to the third. All the furniture was gone. Hay was brought up and scattered on the floor for bedding, with India–rubber sheets and blankets for covering.

“I went down to take a look at the pens. During the day the boys had discovered that a lone slave was locked up in one of them, and lest he might perish of starvation, the trader having fled, they forced the lock, opened the prison doors, and set the captive free. It is said the ignorant Negro declined following his master, but preferred staying with the army.

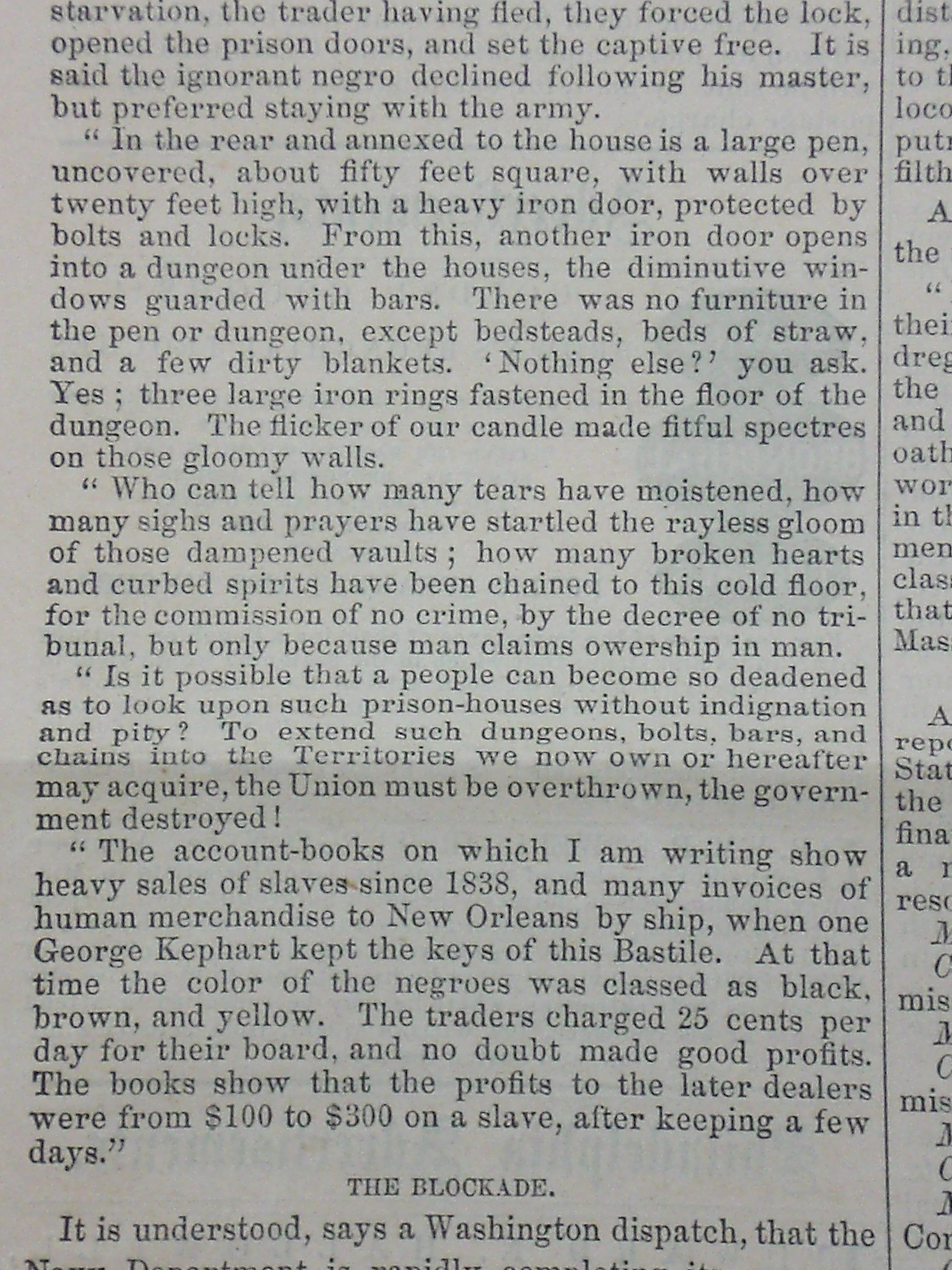

“In the rear and annexed to the house is a large pen, uncovered, about 50 ft. square, with walls over 20 feet high, with a heavy iron door, protected by bolts and locks. From this, another iron door opens into a dungeon under the houses, the diminutive windows guarded with bars. There is no furniture in the pen or dungeon, except bedsteads, beds of straw, and a few dirty blankets. ‘Nothing else?’ you ask. Yes; three large iron rings fastened in the floor of the dungeon. The flicker of our candle made fitful spectres

on those gloomy walls.

“Who can tell how many tears have moistened, how many sighs and prayers have startled the rayless gloom of those dampened vaults; how many broken hearts and curbed spirits have been chained to this cold floor, for the commission of no crime, by the decree of no tribunal, but only because man claims ownership in man.

“Is it possible that a people can become so deadened as to look upon such prison-houses without indignation and pity? To extend such dungeons, bolts, bars, and chains into the territories we now own or hereafter mayor choir, the Union must be overthrown, the government must be destroyed!

“The account-books on which I am writing show heavy sales of slaves since 1838, and many invoices of human merchandise to New Orleans by ship, when one George Kephart kept the keys of this Bastille. At that time the color of the Negroes was classed as black, brown, and yellow. The traders charged $.25 per day of their board, and no doubt made good profits. The books show that the profits to the later dealers were from $100-$300 on a slave, after keeping a few days.”

Here is an advertisement that appeared in an 1832 issue of the National Intelligencer published in Washington DC:

Leave Comment